Is Manotick Ready To Be Plastic-Free?

By Alexa Daddario

Paper straws suck.

As a journalist and environmental scientist, myself, one of my biggest criticisms of the discussion around plastic pollution is the lack of nuance regarding the benefits of plastic. Cheap, durable, and sanitary; plastics have revolutionized industries from shipping and packaging to healthcare, allowing civilization to support greater numbers of people and making participation in society possible for all. Plastic straws themselves are flexible and have lower heat conductivity, which could provide many individuals with disabilities and grip mobility issues a convenient way to consume a variety of liquids.

Previous estimates suggest plastic straws only contribute to plastic pollution by about 4% per piece and about 0.02% by weight. However, that’s still about 8.3 billion pieces, pieces we are sticking right in our mouths and consuming liquids running through them. An easy way to ingest plastics in their most pernicious form, microplastics.

Microplastics are plastic pieces that are less than 5mm in length. Microplastic can be produced directly, such as in the now banned microbeads in cosmetics and oral hygiene products, as well as indirectly through the mechanical or chemical breakdown of larger plastics by erosion, solar radiation et cetera. The largest sources of microplastics are textiles, such as clothing which release microplastics into the water supply when we wash our clothes, and tires which release microplastics from treading.

Microplastics are found in all areas of the globe, from sprawling metropolises to barren deserts, plastic doesn’t just move there by water, but also through the air. Emerging research is finding microplastics in our guts, our lungs and our blood, even breast milk, placentae and brains. For better or worse, plastic doesn’t biodegrade, it just breaks down, getting smaller and smaller until it ends up in our water, food, air and subsequently our bodies.

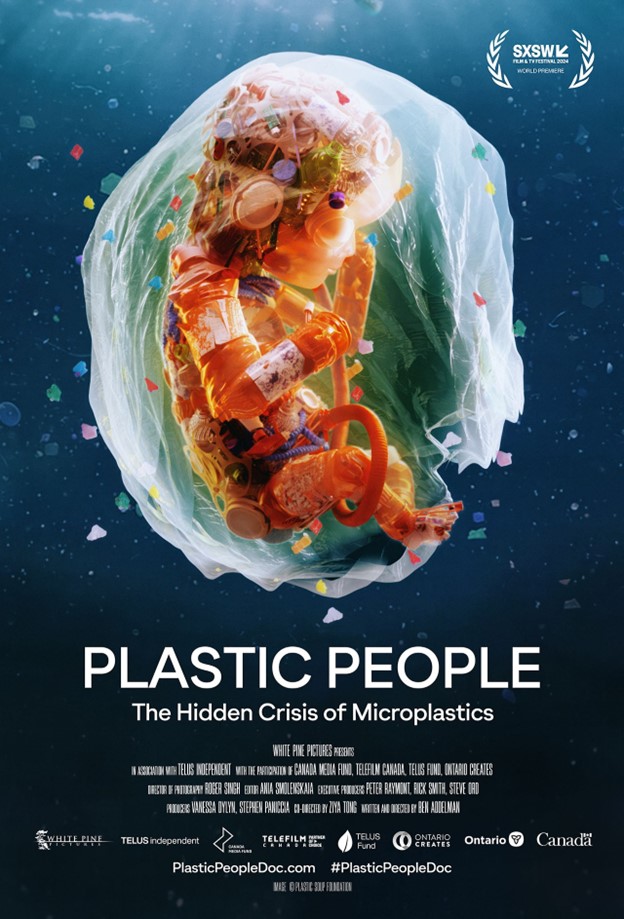

The Intergovernmental Negotiating Committee on Plastic Pollution convened in Ottawa the last full week of April, 2024 with delegates from 175 countries to negotiate a treaty proposal aimed at reducing plastic pollution. The week was kicked off with the premiere of the film Plastic People at ByTowne Cinema, co-directed by Ziya Tong whom many of you will remember as the host of Discovery Canada’s Flagship program Daily Planet, where I had the privilege of completing my internship while a journalism student. Having kept in touch with Ziya, I was fortunate enough to also work on the documentary myself after studying microplastic pollution in Ottawa waterways in graduate school.

Recently, the Federal Court overturned Canada’s single-use plastic ban, citing it too “unreasonable and unconstitutional”. Certainly plastic in and of itself isn’t inherently bad. Plastic is simply characterized as materials synthesized from the polymerization of organic molecules. Humans have been molding natural rubbers for millennia, and before mass industrialization, bakelite and celluloid made up all our shiny new toys.

Today, most plastics are derived from petroleum sources such as oil, coal and natural gas. Additionally, many contain resins, coatings and additives such as phthalates and bisphenol-A.

While the research is still in its infancy, there is some data linking this type of plastic exposure to poorer health outcomes. Phthalates used to soften plastics such as for use in baby bottles have been linked to asthma, allergies and neurodevelopmental abnormalities. Alternatively, bisphenol-A which is used to harden plastic was actually first discovered for its hormone disrupting properties, believe it or not.

In my own research, I found microplastics in 149 of the 150 Rideau River invertebrate samples I collected. While we are far from being the greatest of plastic polluters, and admittedly, many of the substitutions are far more inferior, the question I pose to you, dear reader, is how much plastic are you willing to accept in your food and water?

If you are interested in minimizing plastic exposure in your own life, try using metal, wood and glass, particularly when storing food, and purchasing clothing that uses fabrics with less plastic such as cotton, wool or silk. These are luxuries few of us can afford, however, and ultimately one of the biggest questions raised in Plastic People is whether the onus should be placed on the user or the producer? In which case, writing to elected officials and supporting more plastic aware businesses could make a bigger impact.

Another major insight from Plastic People was the exploration of Bayfield, Ontario. Approximately 80 per cent of eateries in Bayfield have committed to eliminating single-use plastics, becoming the first town in North America to be listed as plastic-free by Surfers Against Sewage, an environmental organization based in the United Kingdom.

Are the residents of Manotick ready to try as well?

Alexa Daddario received both a Master of Science and Master of Journalism degree from Carleton University and Ryerson University (now Toronto Metropolitan University). Her research has been featured in the Marine Pollution Bulletin, Environmental Conservation and the Journal of Biochemistry and Cell Biology, and her reporting in The Canadian Science Policy Centre, ComSciConversation and The Hill Times. Alexa enjoys learning about the environment, animals and fossils, and communicating that information to others. When she’s not doing research or reporting, you can find her reading, doing cartwheels and round-offs (badly), and making dated pop culture references no one understands.

Featured Image: Ziya Tong and Alexa D’Addario at the Canadian premiere of Plastic People at ByTowne Cinema on April 22nd, 2024.