When Al Capone Ruled Manotick

The Torn Down Manotick Tea Room Building May Have Been The Last Connection Between The Village And America’s Most Notorious Bootlegger and Gangster

By Jeff Morris

The walls were barely standing. They were built and then aged, then propped up and rebuilt again over the generations.

Around that building, Manotick rolled by. Generations upon generations of workers, farmers, business people, community leaders, and even Sir. John A. Macdonald have come and gone. A few have left their mark on the village, but most have just faded away.

The common denominator was that building, still known in the village as the Tea Room building.

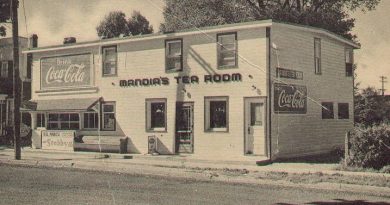

The old Manotick Tea Room, which eventually became Oggi’s Restaurant, and then Manotick Prime, Burgers on Main and finally Lockett’s, was torn down last week. Eventually, a new two-storey office building for Royal LePage will sit on that site. As the building was levelled, the demolition crews literally uncovered one of the most unique time capsules ever seen in Eastern Ontario.

The remains tell a story of Benny Goodman and the big band era, J. Edgar Hoover and Elliot Ness searching for a hidden moonshine whiskey distillery, German prisoners of war, and the notorious gangster and bootlegger, Al Capone.

“I didn’t believe it at first and I thought it was total BS,” said Manotick resident Chris Napior, who owned the building for more than two decades.

“Gus Wersch was the head of the Manotick OPP and then the Nepean Police Service,” Napior said. “That building had been used for a number of things over the years, including the police station. He was the one who first told me about Al Capone. Back in the 1920s and 30s, it was common knowledge in the village. The stories were passed on through the generations.”

Wersch, who was born in 1928, had heard all of the stories. There was a hidden distillery. There was a tunnel underground connecting buildings in the village. And the notorious gangster Al Capone, who made his fortune bootlegging moonshine and beer in the prohibition era, had his fingerprints all over Manotick and a few other Eastern Ontario towns and also in Ogdensburg, NY.

“I didn’t believe the stories about Al Capone in Manotick, but the more people I talked to, specifically the older people, the more stories I heard,” Napior said.

When central servicing was installed in Manotick a decade ago, an unusual discovery was made. An old tunnel under what is now Manotick Main Street was found connecting two buildings.

“Gus had told me there was a tunnel,” Napior said. “When they were digging up Manotick Main Street to put the sewer in about 10 years ago, one of the workers asked me to take a look at something. There were two giant boulders that were at either end of a tunnel connecting the Tea Room building. According to Gus, the tunnel was used to run whiskey between the Tea Room and the Palace Hotel, which was where the Vault is now.”

Prohibition started in Ontario in 1916, a few years before the Palace Hotel burned down.

Manotick’s Pokey Moonshine Distillery

As the village grew in the 1920s, a thriving enterprise existed a few miles east of Manotick. The Pokey Moonshine Distillery was in full operation. Operating in a shack that was hidden in the woods near the Prescott-Bytown railway, whiskey was produced and shipped by rail to Prescott in crates labelled as “Tea”. Spirits produced in Manotick and other Eastern Ontario distilleries were sent to Prescott, where they were shipped across the St. Lawrence River to Ogdensburg, NY.

Prescott was no stranger to whiskey production and exportation. The town was home to JP Wiser and his award-winning whiskey. It was also the main port for importation and exportation between Toronto and Montreal.

At the time, Al Capone was a moonshine bootlegging kingpin. There are debates as to whether or not he visited Manotick and other rural Eastern Ontario communities. It is also unknown exactly how deep his connections are in Ogdensburg. His involvement in the operations in Manotick, Prescott and Ogdensburg, as well as a few other Eastern Ontario communities, were often talked about and still are. Capone’s success was his ability to cover his tracks in everything he was involved in. With Capone’s illegal bootlegging operations operating under the radar, nothing to this day has ever been proven. Capone made sure there was never a paper trail or a shred of evidence about where he was, whether in the US or Canada.

Julie Madlin, who runs ogdensburghistory.blogspot.com, wrote about the bootlegging operation in July. Madlin shared a story about her great grandfather and his involvement in bootlegging across the St. Lawrence between Ogdensburg and Prescott in the 1920s.

“At 5 a.m. on December 5, 1927, Duff Kiah and John Valois, who ran a pool hall, set out across the St. Lawrence River in a rowboat. It was cold and dark with a northwest wind and rough water,” Madlin recalled. “The men were accompanied by another man named Dan Davis. The two men never returned. It was Davis who drove John Valois’ car home when the two men failed to return. Prohibition was in full swing. It was illegal to make, sell, or transport alcohol and all along the border, families were making bathtub gin at home and crossing into Canada to buy booze for resale in their dry hometowns.”

Madlin had also heard the stories of Al Capone’s involvement in the operation, but found nothing to substantiate them.

“There were stories of car chases, crossing the ice with toboggans, punts, and even airplanes. The story of Duff Kiah was not unusual until his disappearance. Duff was my great grandfather, and I grew up hearing stories about him being a ‘hackman’ (a taxi driver and delivery man) and a bootlegger. During Prohibition, Duff, like many other people in Ogdensburg, took advantage of the closeness of Canada to smuggle liquor across the border. Sometimes, according to family legend, he hid bottles of booze underneath a load of stone in his hack. Customs agents did not want to unload the stone to check for alcohol, so he was never caught. Sometimes he took a rowboat bringing booze back and storing it in his shed. He told his children never to go into the shed. Supposedly this liquor was sent to Al Capone, although I found no evidence of this.”

Capone has been tied to almost every community on either side of the border where a distillery once existed. In Canada, Capone is connected to Moose Jaw, Guelph, and a little ghost town in Renfrew County near Eganville called Letterkenny. Yes, Letterkenny. (Gidday Mr. Capone, how are ya now?)

Some reports have Capone using Moose Jaw and Letterkenny as hideouts in the 1930s. However, Capone spent most of that decade in prison at Alcatraz. The connection to Guelph may be more fiction than fact, as Capone is alleged to have been behind bootlegging Sleeman’s Beer from Guelph across the border from Windsor to Detroit, and then shipped to Chicago.

In Letterkenny, it is believed that Capone spent time there in the 1940s after being released from prison. Capone contracted syphilis in the mid-1920s, and the disease had caused brain damage to the extent that he was diagnosed to have the mentality of a 12-year-old when he was released from prison. The closest settlement to where Capone was believed to have spent time an old log structure on the unpaved Letterkenny Road near Quadville, outside of Eganville in Renfrew County.

Capone denied ever stepping foot in Canada, even though Canadian alcohol was the staple of his empire and Pokey Moonshine from Manotick was a major supplier. His famous line was, “I don’t even know which street Canada is on.”

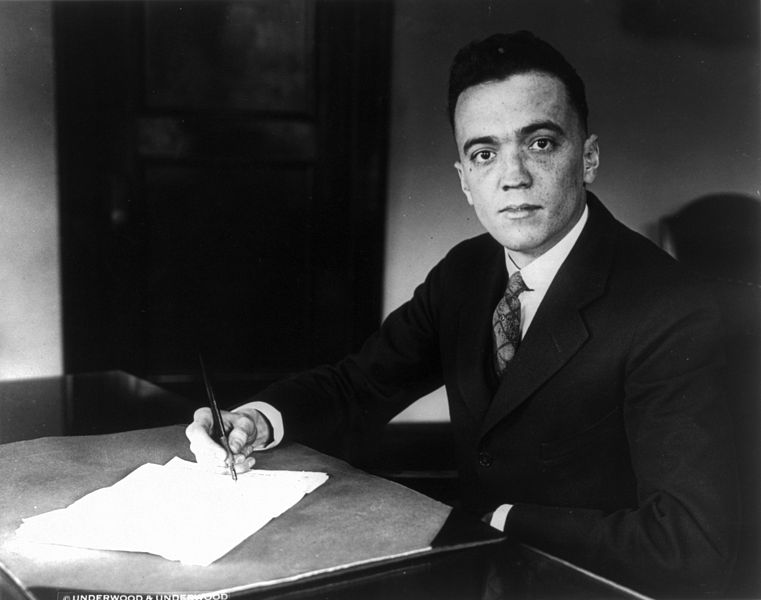

J. Edgar Hoover Visits Osgoode

While it is unknown how much time, if any, Al Capone spent in Manotick, the person who spent his life chasing him definitely had ties to the area and was absolutely in the village.

J. Edgar Hoover, who was the first Director of the Federal Bureau of Investigation, was a nemesis of Capone’s and was intent on taking the mob boss down. He paid a visit to Manotick in the 1920s to visit his cousin, George Hoover, who lived in the area after marrying a girl from Osgoode. Hoover’s right hand man, Elliot Ness, travelled with him. It was Elliot Ness who eventually caught and imprisoned Capone. They couldn’t make a case against him as a bootlegger stick, so Ness got him for tax evasion.

Hoover, who headed the FBI, also headed the bureau responsible for the illegal importation and production of alcohol in the United States.

J. Edgar Hoover may not have been able to venture deep enough into the woods to find the Pokey Moonshine Distillery. Almost a century later, Ottawa historian Andrew King had better luck in finding the remains of the shack that was home to Pokey Moonshine.

“A large black car is said to have taken George and his cousin J. Edgar around the area, most likely in search of the famously secret still providing the US with a lot of ‘tea’,” said King, who has an account of his search for the Pokey Moonshine Distillery on his website, ottawarewind.com.

Andrew King Finds The Distillery

In his story, he shared photos, but chose not to reveal the exact location of where the remains of the shack are.

“Using the information found from researching the story, I headed into the general vicinity of where I thought the hidden still may be located,” King said. “Walking along the long abandoned railway tracks that the whiskey was once transported on, I looked for clues in the area that may reveal some kind of moonshine operation almost a hundred years ago.”

On what King says was a hot sweltering day on a mosquito-ridden path, he found an old rusty metal gate. The gate led to an overgrown path in the woods that led to the ruins of an old log cabin.

“It’s log walls had crumbled away and now lay rotting, but the crude stone foundation could still be seen as well as various metal vessels and pots that were most likely were used in the distilling process,” King said. “Sections of long collapsed tin roofing was strewn around the site that made me suspect that this was indeed the location of the Pokey Moonshine Still.”

Looking around at the remains of the site, King’s heart raced with excitement as he imagined what it would have looked like a century ago.

“Taking a moment to reflect on how this parcel of land may have looked during the Prohibition era I could almost hear the sounds of the men and women hard at work making illegal whiskey, bottling and crating it in ‘tea’ crates to the sound of a distant steam whistle from an incoming train bound for Prescott,” he said.

Wersch, who passed away in 2018, had a theory that while most of the moonshine was produced for Capone’s bootlegging operation and loaded onto trains headed to Prescott and then across the river to Ogdensburg, much of the whiskey used for domestic purposes ended up at the Tea Room. The building was the largest and most popular stop on the road between Ottawa and Prescott and was a main hub in Manotick and the surrounding farms and settlements.

Al Capone and J. Edgar Hoover may or may not have been in the building during their visits to Manotick. At that time, it was a store and snack bar owned by Frank Lindsay and was also home to the local post office.

Let There Be Music

When the building was levelled, there were no tommy guns or rounds of ammunition found.

But when Napior bought the building, there was musical equipment, instruments, albums and drumsticks, which takes the history of the building down another rabbit hole.

Peter and Tess Krupa bought the Manotick Tea Room in 1952. Peter Krupa was from a family that arrived from Poland, with many of his aunts and uncles settling in Chicago. One of Peter’s relatives was Gene Krupa, a famous musician, who by the 1950s was primarily working out of Atlantic City.

The average person would have no idea who Gene Krupa was. For hard core music historians, Gene Krupa is a legend. He was the drummer in Benny Goodman’s orchestra in the 1930s. He revolutionized drumming, and also recorded the first drum solo within a recorded song when Louis Prima recorded ‘Sing, Sing, Sing’ in 1937. In 1982, the song was inducted into the Grammy Hall of Fame.

“We found clarinets and albums and drums and drumsticks – just about everything,” Napior said. “I contacted the Krupas’ granddaughter, and she didn’t know about it and wasn’t that interested. I told her this stuff was a gold mine and I was able to send a lot of it to her.”

Krupa’s influence on drumming was enormous. He is considered the drummer responsible for creating the drumkits that are still standard nearly a century later. He founded a music school and taught many drummers who would go on to fame. One of his students was KISS drummer Peter Criss.

In the early days of television, Krupa was frequently on TV with the rat pack. His drum battles with fellow drummer and good friend Buddy Rich, which were hosted by Sammy Davis Jr., were legendary in the era.

After The War

Before the Krupa’s purchased the Manotick Tea Room, the business was known as Mandia’s Tea Room. Manotick Messenger columnist and local historian Larry Ellis has special memories of Mandia’s in the days when World War II came to an end. Ellis said Mandia’s was “the place to be” on Saturday nights. Mandia’s was the only restaurant in Manotick and was located on the original Highway 16, which was the main route between Ottawa and Prescott.

Ellis said that just after the war, a number of farmers in the Manotick Station/Limebank area employed German prisoners of war as hired help. They helped with the chores and were given room and board plus some spending money. On Saturday evenings, they often went to Mandia’s as a place to meet other prisoners.

“I became friends with four of the prisoners, helping with their English and learned a little German in the process,” Ellis recalled. “We often played cards and the pin ball machines. The war was over and there wasn’t any animosity between the residents of Manotick and the prisoners. I feel I made a friendly difference in the lives of four young prisoners, men in their late teens or early twenties, not much older than me. They realized how lucky they were to be prisoners in Canada, and by early 1946, most had been returned to Germany. This period of perhaps six months is a good memory and an experience I won’t forget.”

The old Manotick Tea Room building is gone now. As construction crews took it down, the memories, ghosts and legends were squeezed out of the remains in the form of dust clouds.

“It’s sad to see that building gone, but it had its time,” said Napior. “It was a central point of the village for more than a hundred years.”

Napior paused for a moment.

“If only those walls could talk,” he said.

Indeed there would have been great stories. But when it comes to Al Capone in Manotick, the walls would probably say they didn’t see a thing.